Today, plans are underway to

celebrate the opening of the new Cos Cob Park. Near the beginning of the last

century, in 1907, a very different opening was in the works on those very

grounds. That is the year the Cos Cob Power Plant opened its mighty doors, and

one man who had been there since the beginning was destined to become the

plant’s chief electrical engineer.

|

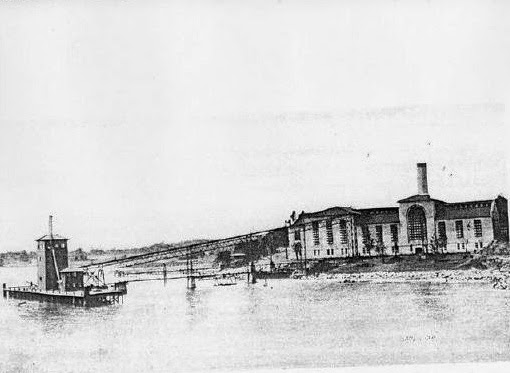

| The Cos Cob Power Plant, 1907 |

|

| Lewis Grant O'Donnell |

In an Oral History Project

interview conducted in 1989 long-time Cos Cob resident, Gertrude O’Donnell

Riska, remembers this man, her father, Lewis Grant O’Donnell, who maintained

overall responsibility for the plant from 1923 until his retirement in 1940.

|

| Gertrude O'Donnell Riska |

When Ms. Riska quotes her

father in her interview, she tends to get her reader’s attention:

“My father would scare me to

death. At different times he’d say to me, ‘See that turbine over there? There’s

a big wheel inside it. If that wheel ever broke loose—and it has in other power

plants—it would cut a path of destruction for ten miles…’”

The turbine she is

describing was one of half a dozen or more, each as big as a house, and between

them were generators weighing fifty tons each. The turbines made the steam that

went into the generators that made the electricity. The turbines and generators

were like “soldiers down a huge hall” and they were “bigger than houses,”

located in bedrock four stories down with support pillars six feet thick. Her

primary impression inside the plant was of heat and noise.

Ms. Riska describes the

plant, owned by what was then the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad

Company, as the first to use alternating current electrification to run the

trains, a claim confirmed by the Historic American Engineering Record. The

plant supplied power for trains “from Long Island, Mount Vernon and the west,

to Cedar Hill, which is beyond New Haven.” Additionally, “it supplied power to

feeder branches to Danbury, New Canaan, and While Plains.” And as Ms. Riska puts

it, running the plant “certainly was not a small undertaking.”

In 1933, the power plant

underwent a critical modernization. The fourteen furnaces were replaced with

boilers, mammoth in size, and each with a fixture to eliminate the smoke and

dust creating such havoc for the community. During all the changes and over the

years, O’Donnell was there. In fact, Ms. Riska recalls never going on family

vacations, except once to the Grand Canyon and one or two trips to relatives in

Ohio. Her father was on call twenty-four hours a day, she says.

|

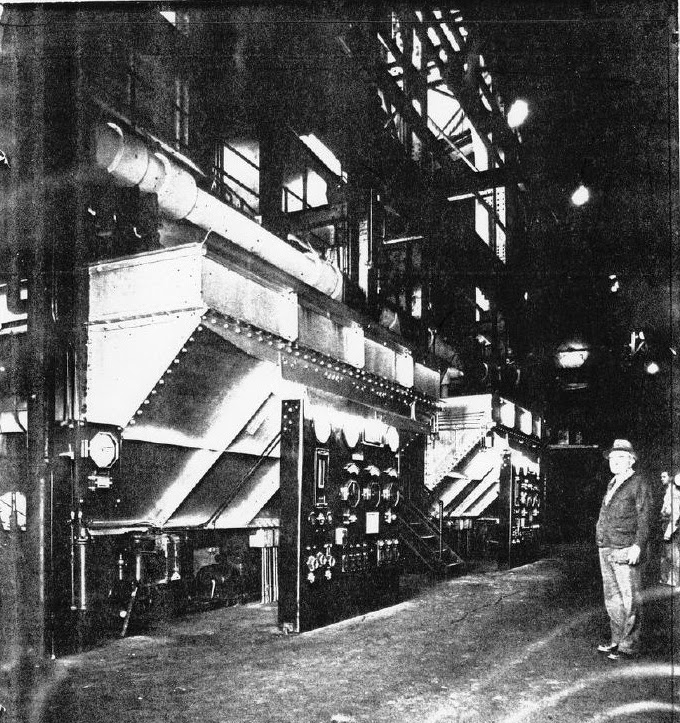

| The four-story boiler room, 1940 |

Costly mistakes and

accidents always a worry, in 1938, after a series of mishaps left Mr. O’Donnell

distressed, he put one of his other talents to work. Not only was he the keeper

of the power plant, he was an artist, and so he created a painting with movable

parts, of racehorses representing different departments. Each horse advanced or

was moved back monthly, depending on the safety record of its department. The

painting hung over the clock with its punch cards. For the next seven years,

after the painting went up, there were no accidents.

|

| The racehorse painting and clock |

Because the plant was not a

place for a little girl to be roaming free, Ms. Riska was well aware of her

father’s boundaries. One day, to her surprise, he told her to climb up several

stairs that had until then been off-limits. At the top was a little slot barely

wide enough to fit a pair of eyes, even a little girl’s. Her father told her to

look through the opening. There she saw a “fairyland,” an enchanted landscape of

shimmering ice and snow crystals. In a place where the heat generated by the

furnaces was maintained at 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit, it was impossible to

imagine ice!

Her father informed her then

that she was looking at white heat and that the glass she was looking through

was very special, inches thick, because, as he told her, “if you looked at it

with your naked eye, it would burn your eyes right out of your head.”

According to Ms. Riska, her

father invented many of the power plant’s regulators and gauges in use until

the plant’s last day. As a result of his many inventions, Mr. O’Donnell became

a member of the National Institute of Inventors in 1920. One of her father’s

most significant inventions was the “piggyback” system.

A little background:

In 1933, when the railroad

was losing business to trailer and lumber trucks, Mr. O’Donnell sat down at his

large “library table” in the living room of their Victorian home. With his

colored pencils and his drafting pads in hand, he set about creating an invention

with the potential of regaining crippling lost business. One day he emerged

from his work, announcing, “I’ve got it. I think I’ve got it solved.”

He had created a system

whereby the trailer of the truck could be detached from the cab and loaded onto

a railway flatcar for rapid transport to the destination. The trailer would

then be reattached to the truck’s cab. It was ingenious—not a way to take over

the trucking business but to “piggyback” on it by using the speed of the rails,

rather than the highway system. The “piggyback” of the plan, of course referred

to the use of the railway flatbed to hold the truck’s trailer.

The plan then went to the

New Haven Railroad. Ms. Riska has a letter, dated March 6, 1933, from New

Haven’s president, which says in part, “I have been greatly interested in

reviewing the papers you brought in covering an arrangement whereby motor

trucks could be transported on freight cars over the railroad.” Ms. Riska’s

father was commended for his plan but heard nothing further.

Years later, according to

Ms. Riska, when in newspapers and books, others were credited with the

invention, her father was crestfallen. He wrote a letter asking for his drawings

and his plan to be returned to him. The reply came back that no drawings or

other materials could be found. In support of her father, Ms. Riska has held

onto the letters and proudly maintains the written proof of his invention.

|

| The power plant, midcentury |

Lewis Grant O’Donnell

retired in 1940 at the age of sixty-eight, three years beyond the usual

retirement age, but even after his retirement, he was called on to set things

right during times of trouble at the plant. He died in 1963 at the age of

ninety-one.

As a final tribute to her

father, Ms. Riska says, “…the day we toured the silent, sad power plant [a tour

conducted in 1988 after its closing], and I looked up at those huge turbines

and miles and miles of electric cables and all kinds of massive equipment, I

just said in awe, ‘How did he do it?’ That day’s gone forever. For a person

with a sixth grade education would not even get his foot in the door unless he

had a degree to throw in first.”

|

| Lewis Grant O'Donnell, on his last day of work, June, 1940 |

Quite an achievement,

indeed.

The Cos

Cob Power Plant was designated a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark in 1982 by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, and it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1990. In spite of its listing, the plant was

demolished in 2001.

Ms. Riska, born November 16,

1919, still resides in her home in Cos Cob.

Gertrude

O’Donnell’s interview, “Chief of the Power Plant,” 1992, is available through

the Greenwich Oral History Project office located on the lower level of the

Greenwich library or in the reference area on the first floor.