Celebrating Black History Month

February is Black History Month, a time to reflect on African

American residents of our town who have made a difference. The Oral History

Project has, over the years, interviewed a number of African American Greenwich

residents whose struggles and accomplishments benefited those who followed

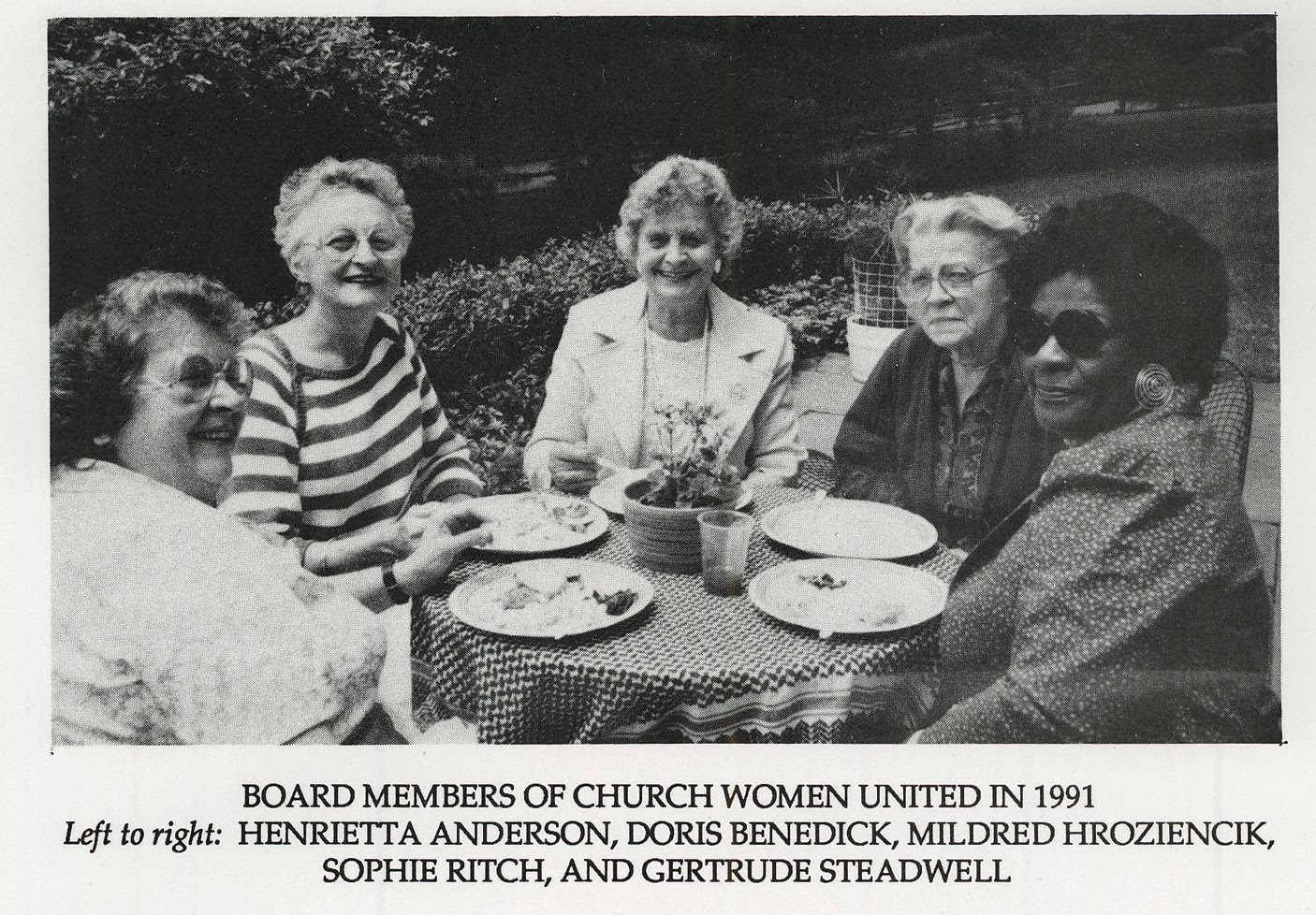

them. One such person is Gertrude Johnson Steadwell, interviewed at the age of

81 in 1990. Gertrude was a determined, strong, capable woman who was not afraid

to do something about racial discrimination when she encountered

it. A proud woman, she broke the color barrier in a number of areas.

Her story is an admirable one to highlight for Black History Month.

In her interview of 1990, Gertrude Johnson Steadwell, born in 1909, says she is happy for the opportunity to tell of the struggles she encountered in Greenwich as an early activist in the civil rights movement. “It was tough going,” she says, but it was worth it. It was really worth it.”

|

| Gertrude Johnson Steadwell |

Longing to become a member of the Camp Fire Girls, she was disheartened to learn that she could not. “Because of my color I couldn’t get in. I was really very disgusted about it,” she says. She was determined from that time on to do something about racial discrimination. She seems to have been born with a gene enabling her to recognize injustice when she saw it, igniting in her a desire to work toward change.

|

| The Maypoles of Greenwich, a favorite memory |

As an adult she seized the opportunity to make a difference. In the late 1930s, she and her husband, Orville Steadwell, joined The Action Committee on Jobs for Negroes, an organization that became a part of the Greenwich chapter of the NAACP, of which Gertrude and her husband were founding members. She also formed the Southwestern Connecticut Committee on Fair Employment Practices. Her work led to a bill being passed in the state legislature ensuring fair employment for blacks. “This was the biggest thing I’ve ever done,” she says of this period in her life.

In the midst of all her work to enhance workplace opportunities, Ms. Steadwell found time to raise a family of four, to break another color line becoming an interior decorator in Greenwich, being a member of many civic organizations, an active member of her church, and a recognized community leader.

Looking back over the years and the changes that have occurred, Ms. Steadwell concludes in her interview that much has changed for the better. She cites improved employment opportunities and improved choices, much as a result of affirmative action. Her own children were able to see the fruits of these changes having achieved good educations and jobs.

“I’m really glad that I could tell you,” she tells our interviewer. “I figured one day it would come in good. Not for me, for my children, I was thinking.”

And “good” for the many others who followed after her, in the path she helped to clear.

Gertrude Johnson Steadwell died in Greenwich, August 15, 2007, at the age of ninety-eight.

The Oral History Project book, A Civil Rights Activist: Gertrude Steadwell, is available for $10 in the Oral History Project office of the Greenwich Library.