Celebrating Black History Month

Several years ago, we celebrated Black History Month by highlighting interviews from our collection. Among those were interviews with Alberta E. Bausal, who told her story of community and church; Andrew and Louise Blackson, who recounted their experiences in Greenwich over the years; Eugene J. Moye, Sr., who told of being the first African American police officer in Greenwich; Winston Robinson, who related his experiences as a former president of the NAACP in Greenwich; and many others. This year it seems fitting to reprise a post about two African American women of strength and resolve who were once residents of our town.

One woman who recounts a long life filled with hardship and joy, all with no complaints, is Louise Van Dyke Brown. From the beginning she is resolute. A woman of strength and accomplishment, she is most proud of the independent life she has lived. One suspects her independence as largely the result of her ability to make the best of every challenge she encountered.

Louise Van Dyke Brown was born in Greenwich on February 25, 1893 and was interviewed by one of our volunteers for the Oral History Project in her home the summer of 1977 when she was eighty-four.

|

| Louise Van Dyke Brown |

Her parents, she says, though not born in Greenwich, came early, met young, and were married in 1889. She counts her family among the first black families of Greenwich.

From the start Ms. Brown tells of a life of hard work and sacrifice, all without a trace of resentment. The second of seven children in the family, Ms. Brown dropped out of school at fifteen in order to help support the family but primarily to help her mother who worked long hours and who took in laundry to make ends meet. While several of her surviving siblings went on to graduate from high school, an accomplishment in itself in those days, Ms. Brown, in spite of her quick mind, never had that privilege. If there was one regret, it was that.

Not one to linger on life’s disappointments, she also tells of a happy childhood, filled with friends, black and white, of little or no segregation, and of a carefree, fun-filled Greenwich. There may not have been money to waste or a home filled with anything beyond the bare necessities, but life, as Ms. Brown recalls, was good.

She does not skirt the truly sad times, though. There was the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 that saw her family members sick and feverish, with Ms. Brown ministering to them as though she were a nurse. There is the heartbreaking rendering of her little sister, rising from her bed in the throes of death while her older sister rushes from the house to find the doctor, only to have her sister die in the process.

Ms. Brown married Granville Brown in 1919 and spent her life working in various capacities in Greenwich and being a vital member of the church, Bethel A.M.E., which her grandparents and father helped to found.

Ms. Brown married Granville Brown in 1919 and spent her life working in various capacities in Greenwich and being a vital member of the church, Bethel A.M.E., which her grandparents and father helped to found.

If life had been otherwise, she may have added an education and a career as a nurse to her accomplishments, but since that was not to be, she did not look back on her long life with anything but gratitude for her health, her family, friends, and her church.

Near the end of her interview, she tells of a happy life with her husband, until his death in 1952, and she says, “I love my home. I love Greenwich so much. I told everybody I’m never going to leave it. My grave is bought…by my mother and everybody. I’ve prepared for myself, and I take care of myself.”

Louise Van Dyke Brown died in Greenwich three years after this interview, June 7, 1980.

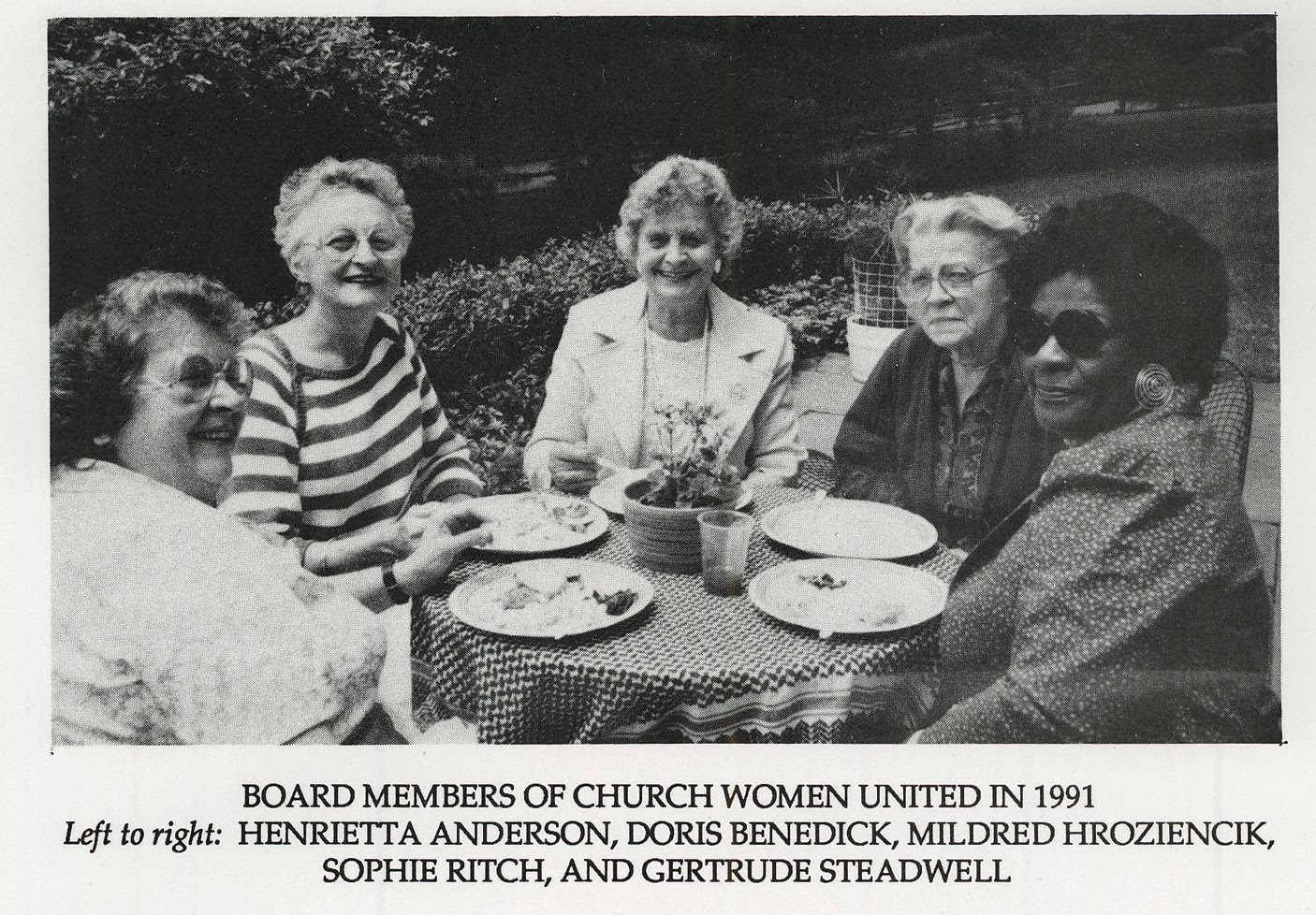

In her interview of 1990, Gertrude Johnson Steadwell, born in 1909, says she is happy for the opportunity to tell of the struggles she encountered in Greenwich as an early activist in the civil rights movement. “It was tough going,” she says, but it was worth it. It was really worth it.”

|

| Gertrude Johnson Steadwell |

Longing to become a member of the Camp Fire Girls, she was disheartened to learn that she could not. “Because of my color I couldn’t get in. I was really very disgusted about it,” she says. She was determined from that time on to do something about racial discrimination. She seems to have been born with a gene enabling her to recognize injustice when she saw it, igniting in her a desire to work toward change.

|

| The Maypoles of Greenwich, a favorite memory |

As an adult she seized the opportunity to make a difference. In the late 1930s, she and her husband, Orville Steadwell, joined The Action Committee on Jobs for Negroes, an organization that became a part of the Greenwich chapter of the NAACP, of which Gertrude and her husband were founding members. She also formed the Southwestern Connecticut Committee on Fair Employment Practices. Her work led to a bill being passed in the state legislature ensuring fair employment for blacks. “This was the biggest thing I’ve ever done,” she says of this period in her life.

In the midst of all her work to enhance workplace opportunities, Ms. Steadwell found time to raise a family of four, to break another color line becoming an interior decorator in Greenwich, being a member of many civic organizations, an active member of her church, and a recognized community leader.

Looking back over the years and the changes that have occurred, Ms. Steadwell concludes in her interview that much has changed for the better. She cites improved employment opportunities and improved choices, much as a result of affirmative action. Her own children were able to see the fruits of these changes having achieved good educations and jobs.

“I’m really glad that I could tell you,” she tells our interviewer. “I figured one day it would come in good. Not for me, for my children, I was thinking.”

And “good” for the many others who followed after her, in the path she helped to clear.

Gertrude Johnson Steadwell died in Greenwich, August 15, 2007, at the age of ninety-eight.

The Oral History Project books, Louise Brown: Church and Community and A Civil Rights Activist: Gertrude Steadwell, are available for $5 in the Oral History Project office of the Greenwich Library.