Dr. Lee Losee Davenport and the Development of Radar in World War II

CELEBRATING FIFTY YEARS OF THE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT

In

November 1940 Lee Losee Davenport, a twenty-five-year-old PhD student in

physics at the University of Pittsburgh, received a call from the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology “about a secret project…he couldn’t tell me what it

was, but he wanted me up there immediately.”

|

| Dr. Lee Losee Davenport with World War II identification and memorabilia. Courtesy of Greenwich Library Oral History Project. |

The

group at MIT consisted of thirty college professors, “heads of physics

departments of important colleges here, as far west as Chicago.” They called

themselves the “Radiation Lab,” a cover name to hide the real purpose of their

study, to develop anti-aircraft radar. Davenport came to the conclusion that he

was included in this elite group because he had worked with one of the

professors from the University of Pittsburgh who knew that “I was responsible

at Pitt for making some of the most complex equipment for my thesis.” Davenport

continued, “My role in this project was to get this thing built…the think tank

was the idea men, the Einstein-type people… How to reduce that thought into a

piece of machinery, or a piece of radio equipment, was up to other people, and

I think that is one of the reasons I was chosen…I built x-ray tubes and so on.

And I think he viewed me as a scientist who knows how to build things.”

Dr.

Davenport was interviewed by Oral History Project volunteer Janet T. Klion in

2008 at the age of 93. He described his experiences as a member of the

Radiation Lab, and their invaluable contributions to the development of anti-aircraft

radar, instrumental in the Allied victory in World War II.

As

Davenport described it, the secret tasks of the Radiation Lab were twofold.

Firstly, “to take a magnetron…and see if you could make a radar device small

enough to fit in the nose of an airplane. In that way they hoped to be able to

find the German fighter planes or bombers at night, that had been bombing

London with serious damage.”

Davenport

was assigned to Project Two, “to see if you could make a radar system that

could operate in all weather, pick out airplanes – a single airplane – and follow

it automatically so that it would be accurately possible to aim an

anti-aircraft gun at the plane and shoot it down.”

RADAR,

the acronym which stands for Radio Direction-finding and Range, “travels

at the speed of light…and you have to measure time to that accuracy to be able

to find out how far it is. You have about a hundred-millionths of a second to

measure the time.” After three months of work on the project with radar, it was

possible to find an airplane. “In May of 1941, seven months before Pearl

Harbor, “we had a system that worked on the roof of MIT, which we could follow

an airplane with, track it automatically, follow that plane without human

help.”

The

Signal Corps was impressed with this equipment and gave instructions for it to

be transported to the Fort Hancock Proving Grounds in New Jersey. To do so, it

was necessary to fit the apparatus into the body of a truck. “I drove it down

myself, on the Merritt Parkway” with “an armed guard sitting alongside me.” It was

tested on December 7, 1941 and “we had a working machine.” After a few changes,

it was sent to the headquarters for the anti-aircraft command in Virginia.

After additional tests, the military decided to buy it “right then and there.”

The project was now named SCR 584 (Signal Corps Radio 584) and General Electric

and Westinghouse were instructed to each build 1700 of them. The instructions

to these companies were, “Don’t change a thing. You’re to reproduce exactly

what the Radiation Lab people are showing to you, and we want them right away.”

Exterior view of SCR 584

(Signal Corps Radio 584).

Contributed photo.

The

first practical use of this anti-aircraft device “occurred in England. One of

them was shipped over. I was over there with it, and a German aircraft came

over Scotland, and we knocked him out of the sky, right away.” Its first use in

combat occurred “at the Anzio beachhead (in Italy in early 1944) when “the two

584-directed gun batteries shot down nine out of the twelve planes that the

Germans had tried to use.”

The

most significant use of SCR 584 occurred on D-Day, June 6, 1944 “when we

invaded the Normandy coast.” The challenge was to get the equipment there to

protect our troops. “Now that was a major effort. This is a semi-trailer loaded

with equipment and they had to get them ashore at, or a day after, D-day.”

Nineteen of them were waterproofed in Wales to be floated ashore. “I was there

to design and work that out and they did get ashore very promptly, and helped

to defend our troops. We knocked down a lot of planes.” By the time the war

ended, “we were tracking our own airplanes...and I was working on beacons and

other systems which we used to steer them, with maps inside the 584s.” Overall,

Davenport concluded “that about a thousand German aircraft were knocked down by

anti-aircraft fire, all of which was directed by SCR 584 radars…After that,

they became used widely everywhere in the Pacific.”

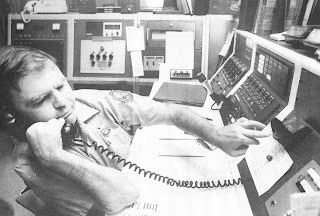

Interior view of the SCR 584 radar tracker

that guided pilots to their targets.

Contributed photo.

Before

joining the Radiation Lab at MIT in 1940, Lee Losee Davenport had completed his

course requirements for his doctorate at the University of Pittsburgh but had

not written his thesis. In 1946, The University of Pittsburgh granted Davenport

a PhD based on his classified work at MIT. “So, I got a PhD on a secret

project, and it was a secret for twenty-five years after World War II ended.”

Davenport mused: “I have been the luckiest guy in the world. It was luck that I

got singled out to go to the Radiation Lab.”