Andrew Bella

From Byram Boy to High School Principal

by Mary A. Jacobson

There aren’t too many residents of

Greenwich who can trace their ties to the Greenwich Public Schools from their

earliest childhood years at New Lebanon School to their retirement after a

career spanning forty years. Such a man was Andrew Bella for whom Bella House

at GHS is proudly named.

Andrew Bella.

Courtesy of the Oral History Project.

Bella’s description of his early school

days at New Lebanon were far different from those experienced today. “We had a

crowded school even when I was here, and we had to use the church on William

Street for some of the classes.” Bella’s favorite game of baseball was played

on a field where the ashes from the school furnace were disposed. “The

playground actually was just the open field with stones for bases and ashes in

the outfield . . . We passed the hat and made enough to buy the

balls and bats and the equipment we needed. So that was the Recreation and

Parks Department!” As Bella recounted, “No one had a car. My dad didn’t have a

car till I was sixteen (in 1923). Cars and airplanes were a novelty. If you’d

see a plane, everybody would look up.”

From New Lebanon School, Bella went to

Greenwich High School, which was located on Havemeyer Place. However, for

Bella, there was “no gym, no yard, no nothing.” For physical education, the

students would do calisthenics in the third-floor hallway. “Weather permitting,

we would run around the block.” There was also no auditorium. For assemblies,

Mr. Folsom, the principal affectionately known as “Pop,” would climb on a

platform in the corridor “and we would stand around him, and we’d have our

assemblies there.” The year Bella graduated in 1925, however, construction

began on the new high school on Field Point Road (now Town Hall).

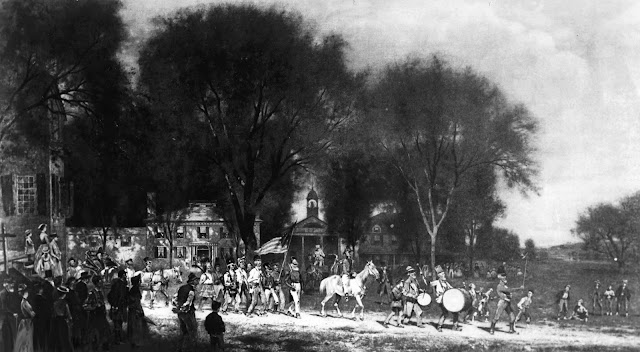

Havemeyer School, on Havemeyer Place, eight years after its opening in 1892.

Site of the first Greenwich High School graduation in 1895.

Courtesy of Greenwich Library.

By 1940, with a master’s degree in

educational administration from Columbia, Bella was named principal of

Greenwich High School. During his tenure, until his retirement in 1969, the

high school experienced much growth and development. “The athletic program

evolved from football, baseball, and basketball into the complete spectrum of

sports we have today (1977 at the time of interview), including lacrosse,

tennis, and soccer . . . We developed ice hockey when the rink

was built in Playland . . . We were the only out-of-state school

that skated in Playland. Many times we were champs of the Westchester County

Hockey League.”

Bella also supported increasing school

services for students who had learning difficulties or were academically

challenged. “The whole guidance movement developed during my tenure at the high

school.” Bella was also particularly proud of a program developed in the

aftermath of World War II. “Boys who had not finished their high school education

were allowed to come back as veterans . . . they were the best

students; they knew what they wanted to do.”

As the post-World War II baby-boom

generation moved through the school, its facilities became cramped with some

classes held in the auditorium and gymnasium. “Toward the end of my career at

Field Point (now Town Hall), our proms were so large that we had to have two

orchestras. We had one inside the girls’ gym and we had a tent on the front

lawn, so there was continuous music inside and outside.” “Afterglows”

(post-prom gatherings) were held at The Clam Box in Cos Cob so the students

would have a place to go after the prom.

Bella fondly recalled an incident in

which he was summoned to the second floor because there was a car in the

hallway. “A crowd of maybe a hundred students followed me up and, sure enough,

there in the corridor was this Volkswagen completely assembled . . .

What they had done is, during the night, under blankets with flashlights, taken

this car apart, and hoisted it up to the second floor . . . no

gasoline . . . no scratches . . . They did it and

they were fine students.”

Bella had definitive views about the

value of discipline. “I think that discipline, if it’s fair . . .

is something that students want . . . If they don’t have it,

they’re going to look for it, and they’re going to look for it by doing

something that demands discipline . . . Youngsters want to know

what the lines are.”

Greenwich High School on Field Point Road in 1960.

Opened in 1925.

Now serves as Greenwich Town Hall.

Courtesy of Greenwich Library.

The interview entitled “From Byram Boy to High School Principal”

may be read in its entirety or checked out at the main library. It is also

available for purchase at the Oral History Project office. The OHP is sponsored

by Friends of Greenwich Library. Visit the website at glohistory.org. Mary

Jacobson serves as blog editor.

|

| Andrew Bella. Courtesy of the Oral History Project. |

|

| Havemeyer School, on Havemeyer Place, eight years after its opening in 1892. Site of the first Greenwich High School graduation in 1895. Courtesy of Greenwich Library. |

|

| Greenwich High School on Field Point Road in 1960. Opened in 1925. Now serves as Greenwich Town Hall. Courtesy of Greenwich Library. |