Last March our volunteers commemorated the opening of

the Cos Cob Park by going to our archives and highlighting here an interview

conducted in 1989 with Gertrude O’Donnell Riska. Her interview is largely a

retelling of the time her father, Lewis Grant O’Donnell, had overall

responsibility for the Cos Cob Power Plant from 1923 until his retirement in

1940, long before the plant was demolished in 2001.

|

| Gertrude O'Donnell Riska |

Much has transpired since last year. This past summer

the Cos Cob Park won the 2016 Sustainability ACE Award and the 2016

Environmental ACE Award of Merit from the Connecticut Society of Civil

Engineers (CSCE). In September, on the fifteenth anniversary of September 11,

2001, the town hosted a remembrance ceremony at the new 9/11 memorial in the park.

|

| September 11 Memorial, Cos Cob Park |

But before these events, on March 18, 2016, just days

before the park’s first anniversary, Gertrude O’Donnell Riska died, surrounded

by family in her Cos Cob home.

Given these events it is fitting that we turn again

to her interview, and the writer responsible for this year’s visit is a new Oral

History Project volunteer, Olivia Luntz, a Greenwich High School senior. We are

pleased and honored to publish her first blog entry below.

Cos Cob Park Today

By

Olivia Luntz

Walking through

Cos Cob Park today, one could never imagine the huge significance the piece of

land once held. When walking on the fields, hearing kids laugh on the

playground, or skipping stones into the harbor, one would not think the now

peaceful place was once essential for all train movement in New England. A

century ago the site of Cos Cob Park held “the world’s first experimental

station to use alternating current electrification to run trains.”

The unique

location of the site was essential for the power plant, as the area has access

to fresh and salt water, as well as access for barges, and proximity to New

Haven and New York. Originally the plant supplied power to run trains from Long

Island to New Haven and also gave power to feeder branches in Danbury, New

Canaan, and White Plains. This huge undertaking occurred in the heart of Cos

Cob and was staffed by fewer than 150 men, working around the clock. For the

Chief of the Power Plant, Lewis Grant O’Donnell, the responsibility to provide

Connecticut trains with power required many sacrifices. His daughter, Gertrude

Riska, describes it as “a twenty-four hour job, whether he was there or at

home….During emergency calls he would have to go at night.” The power plant

opened in 1906 and O’Donnell was there from the start. He was eventually

promoted to chief electrical engineer in 1923, a position he held until he

retired in 1940, after working for the plant for 34 years.

|

| Lewis Grant O'Donnell |

Riska’s

descriptions paint a vivid picture of the power plant. It was built four

stories down into bedrock, with six-foot thick support pillars, and walls of

two-foot thick reinforced concrete, while the floor was four feet thick. The

turbine room was five to six stories high, with six to eight turbines the size

of a house sitting in a row, and she recalls, “The minute you stepped inside

you were engulfed in heat and noise.” The generators between the turbines produced

the electricity. If one of the huge wheels inside of one of the turbines ever

broke loose, which had happened in other power plants, “it would cut a path of

destruction for ten miles…to the other side of Port Chester and destroy

everything in its path.”

On a more

cheerful note, the plant also housed hidden treasures. For example, on the wall

where the workers’ timecards were kept there was a beautiful clock and above

the clock was a mural that O’Donnell had painted himself in 1938 after several

accidents at the factory. The mural was six feet long and three feet high and

depicted a racetrack. It featured cutouts of horses, which were movable from

the start line to the finish line. “Each department was represented by a

racehorse, and they advanced or retreated according to their careless accidents

for the month. Among the horses was a donkey named Carelessness. He represented the

lowest score. And the winning department got awards.” The poem above the mural

read “Our racehorse Safety who is fast on his feet/Can beat old Carlessness whenever they meet/So give him your support--obey all the rules/By taking no chances when working with tools.” Over the next seven years the competition between

all of the departments was so intense that no accidents occurred at the plant.

Riska believes that the mural and clock have since been taken to the

Smithsonian. She recalls that the Smithsonian also claimed the plant’s

switchboard “with its gleaming brass dials and rows and rows of gauges and

needles….It was beautiful….Some of those dials dated back to nineteen hundred

and they were still working when the plant closed [in 1987].”

|

| Racehorse painting above the clock |

Along with

caring for his workers’ safety, O’Donnell also fought to keep his workers’ jobs

during the Great Depression. When informed that twenty of his men had to be

laid off, he was distraught. All of his workers had children and there were no

other jobs available. He asked if they would take a cut in pay to keep everyone

working, but many who had been working at the plant for years claimed seniority

and asked O’Donnell to fire the newer workers. O’Donnell, however, had a

different strategy in mind. The next day he re-gathered the workers, and

standing at the top of the stairs, he announced, “I have a hat in my hand which

contains slips of paper with each man’s name on it…the first twenty names

[pulled out] are the men that will be laid off.” As none of the workers wanted

to rely on luck, they all agreed to the pay cut and no one was laid off.

O’Donnell saw these workers as his family and could not let any of them go.

According to

Riska, the most exciting events at the plant were the several times a year when

a deep sea diver would go down to clean the flumes. Barnacles growing on the

sides of pipes would, over time, block the flow of water to the plant. “The

diver sat on an old wooden bench, the huge suit was put on him…then the heavy

over boots each weighing fifty pounds. That’s so when he got down to water, he

wouldn’t float; he would be upright. Then, lastly, the headpiece and the

breastplate….At this point, the tender would start the air flowing, by using

this little hand pump. The diver would shuffle—he couldn’t walk because the

shoes were too heavy—over about ten feet to the open manhole. And he did look

like Frankenstein.” From there, as Riska explained it, he would wave up and

disappear into his work. The task of scraping all of the barnacles off took a

few days.

Other important

events at the plant included the 1938 hurricane, in which the tide rose so

quickly and so forcefully that it swept up the flume, short-circuited the

plant, and flooded the lower floors. O’Donnell did not leave the plant for a

week, until he was able to get the trains running again. Later, during World

War Two, the plant was guarded by F.B.I agents, because if the plant were bombed,

there would be no train movement in or out of New England. Additionally, an armed

guard protected the plant from a shack under the Riverside railroad bridge. His

job was to stand, rifle in hand, whenever a train came along.

|

| Power Plant Boiler Room |

Outside of the

power plant O’Donnell also made a major impact on the Cos Cob community. He was

one of the founders of the Cos Cob Fire Department and built the first pumper

for the fire patrol. He also drew the plans for the present firehouse and

raised the money to build the firehouse. O’Donnell also used the burned coal

residue from the plant to fill in a swamp in Cos Cob, which is now part of the

Cos Cob School playground, and created a mini-park beside the Cos Cob

firehouse. “My father had established many flower beds where beautiful giant flowers

thrived in a mixture of fly ash and soil. The paths were neat and edged with

whitewashed stones. At Christmas time there were at least ten Christmas trees,

ablaze with colored lights, a lovely sight for the people to see from the

trains.”

O’Donnell

retired as chief electrical engineer in 1940 and the power station was

decommissioned in 1987. Although the plant was added to the National Register

of Historic Places in 1990, it was demolished in 2001, after a local and

national debate. If you ever find yourself in Cos Cob Park today remember that

what is now a beautiful place for children to play was once capable of powering

trains across New England. More importantly, however, remember Lewis Grant O’Donnell and the lessons that we could

learn from his life, such as his dedication to his job and community and his

commitment to the wellbeing and safety of all of those around him.

Gertrude O’Donnell’s

interview, “Chief of the Power Plant,” 1992, is available through the Greenwich

Oral History Project office located on the lower level of the Greenwich library

or in the reference area on the first floor.

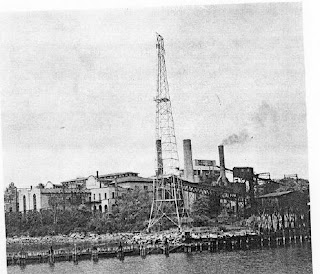

|

| The Power Plant at Mid-Century |